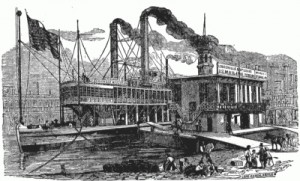

Cutting Wood for the Mississippi Steamboats

I am the very fortunate holder of several pieces from my mother, the sort of gold that genealogists yearn for. I have three taped interviews my mother did, two with her father and one with a “cousin”, all about their memories and stories from the past. I also have an autobiography written by my mother. These are sources of information that I might not/would not have had otherwise. So I am grateful and have been known to encourage friends and acquaintances to create their own interviews while the opportunity exists. If you have a parent, aunt/uncle, older cousin, even older sibling – consider asking for stories that person remembers from childhood and asking to record the stories. Having my mother’s voice and my grandfather’s talking about times past is priceless, as the commercial says.

The focus of this post is one of the interviews done with my grandfather, more than twenty years ago when he was in his 80s. I not only have the tape (and have digitized it), but I had it transcribed. My goal is to present the individual stories my grandfather told, adding a little context and maybe a picture or two. The story today is one he told about his grandfather’s experience as a young man hiring out to chop wood. My grandfather, Lyle Denman, lived from 1896 to 1997. His grandfather, Charles Minor, lived from 1837 to 1913.  The family lived in north-eastern Ohio in a village called Wakeman in what is now Huron county, just south of Lake Erie (the small black unlabelled dot in north eastern Ohio on the map).

The family lived in north-eastern Ohio in a village called Wakeman in what is now Huron county, just south of Lake Erie (the small black unlabelled dot in north eastern Ohio on the map).

Grandpa Minor lived with Lyle’s family from about 1900 to 1905, when my grandfather was about ages 4 to 9. The arrangement was that if my grandfather was good, and didn’t bother his grandfather unduly during the day, then he would be told a story toward the end of the day. Here’s one my grandfather remembered and told my mother, about when his grandfather was a young man before the Civil War (probably sometime between about 1853 and 1860, when he was between 16 and 23):

“In the winter time there was absolutely no work for young men around Wakeman, just a case of waiting for spring planting. Once the fall crops had been harvested, there’d be several months that they had to wait without much to do. One year, my grandfather saw an ad in the Cincinnati Enquirer asking for woodcutters along the Mississippi to prepare wood for the steam boats. Grandfather and another young man, paid their way to Cincinnati, where they were picked up by the corporation wanting the wood cutters, and taken to Memphis by steamboat where the headquarters of the logging company was.

On the way down the river, all the passengers lived up on the second deck. Down below, they would stop at the various little hamlets and towns and maybe take on a cow or some chickens or something that was to be sold at New Orleans or down river someplace. And all of the deck hands that handled that stuff were black. And the waiters that waited on the tables for the passengers on the second floor were all black. There was ample food and great quantities of it were served and there was always a lot of it left over on the table. Following each meal, two of the black hands, or four, would appear with two tubs. One tub was for dishes. The other tub was for uneaten food. Every bit of food that was uneaten was scraped into a tub. The dishes were put in another tub. The uneaten food was taken to the lower deck where the deck hands, with their fingers, helped themselves and that was how they were fed. They were fed with the unused portion of the meal from the passengers above. It doesn’t sound too sanitary. But then, that’s the way it was in those days.

Arriving at Memphis, they were signed on and taken down the river in a smaller boat to a certain place. I could have been mistaken, whether it was Memphis or Natchez, but I think it was Memphis. At any rate, the headquarters of the wood cutters were there and the two men were each given a rifle, a blanket or two, some blankets, and the boat that took them down had provisions. They had salt pork, sow belly as they called it, and corn meal and coffee and beans. They were given a rifle, a light weight rifle with ammunition. And when they were finally established at a certain place, I think it was someplace in Mississippi along the river, they were told to make camp.

They were given a tent to live in and they made camp and were told how to prepare the wood. It had to be cut in — I think it was four foot lengths. And they were paid so much a cord for the wood, and every two weeks the supervisor’s boat would come by and measure up the amount of wood that they had cut. Cottonwood was the main wood that they cut. And it had to be piled on the bank where it could be loaded. When the steamers needed it, they would lower their gangplank and the crew would carry the wood on board to take them to the next station, wherever they needed it. And the men would always take their rifle with them and sometimes they would shoot a wild turkey or shoot — one time they shot a deer. And they feasted on the meat as long as it was good. And they learned how to trap wild turkeys. They found a supply of ear corn and they would shell off a few handsful of corn. They would dig a trench that got a little bit deeper and deeper along. And then over the end of that trench they would build a house of saplings, just little sticks cut and laid across each other to make a house big enough to hold a turkey or two at the end of this trench that they’d dug. And as the trench deepened, the turkeys — they would string the corn, one kernel at a time following the other and the turkey would begin eating and would eat his way down to the end. And when he reached the end where there was no more corn, he’d raise his head up in the air and try to get out. He didn’t know enough to duck his head down and go out the same way he came in. And he was trapped inside of the little homemade trap that had been made which was nothing more or less than saplings criss-crossed and made into a little house. And in that way they provided themselves with turkey and occasionally they would shoot quail or other food. And that’s the way they provided their food.

And for water they had two buckets or more. Each morning they would fill a bucket of water out of the Mississippi River and set it to settle. It was always muddy and murky. And it would settle until evening. When evening would come, they would pour off the top and that was the water that they had to drink. First, though, they would boil it. They had to boil it and let it cool. And at night they always had a bucket or two of water setting there ready for the mornings to repeat. The mud and sediment would settle to the bottom and they would pour off the water, boil it, and make use of it in their coffee or drink it. That was their drinking water. After they had been there for — they went down in the fall perhaps — he didn’t say or I don’t recall what month. It could have been November or October — after the local harvest : apples and corn had been harvested in Ohio — is when they went down there. And they stayed until along in the spring, perhaps the month of May. That was not — I do not recall his exact time that they decided they had been there long enough. So when the supply boat came, they told them that the next week they would break camp and wanted to return home. Which was accomplished. They were taken to the — they had all they needed. They had no money or anything. But the supply boat, the inspector or the manager would give them a receipt for so much wood cut and piled each time he came along. And those receipts were taken to the office and they collected their money and returned home.”

0 Comments on “Cutting Wood for the Mississippi Steamboats”